Beneath the big sky

September 3, 2011

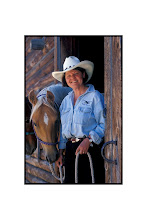

Home on the range ... guests can participate in the working life of ranches. Photo: Getty Images

Lance Richardson saddles up and joins 'dude cowboys' on a working ranch in wild Montana.

The clouds are low with rain but we've gone out riding anyway. While the horses struggle up stony foothills, white-tailed deer raise their heads in alarm and scatter through the sagebrush. There are few birds about; the paralysing beauty of the Montana wilderness creates an impression of unnatural quiet. The only sounds I recall are hooves in mud, snorting animals and the roar of a creek swollen with snow melt.

After a long time we reach a bluff, its steep edge overlooking a wide valley of patchwork fields punctuated by red barns and lines of Douglas firs. I ask Mike Leffingwell, the ranch owner, if the snowy peaks in the distance are those known as the Crazy Mountains. Leffingwell pulls up his horse beside my palomino and nods. The "Crazies" are something of a local legend, he'd told me earlier, spittoon wedged between his legs as he drove the pickup one-handed down an unsealed road.

Advertisement: Story continues below

As white settlers moved westward across the US, the native inhabitants were forced from their homes and often killed. One woman, after watching her family die, climbed up among the mountains and went insane. On a violent day the wind carries the sound of her endless wailing across the valleys.

Told anywhere else, such a story would be shrugged off as a fantasy of the "wild west". Here, however, Leffingwell recites it without comment. Here, where mountain men once traced Indian trails to lead Conestoga wagons to safety, where wolves still prowl right past the front door, strange tales are part of a strange land. In some parts, the wild west was only a hundred years ago, if it ended at all.

To reach G Bar M Ranch, Leffingwell's working property just outside the town of Clyde Park near the Yellowstone River, I drive down a long road through a twisting valley, then into a field filled with yellow daisies. There are about a dozen buildings at the end, but the heart of the ranch is an impressive structure of stacked, burnished logs known affectionately as "the lodge". Maria, Leffingwell's wife, "skinned" many of the logs herself, a herculean effort that leaves her grimacing with phantom pains whenever it's recalled. Walking up its steps I notice antlers collected on the front porch (they were shed naturally and collected on the property) and, just inside, a bear skin draped behind a mounted bald eagle. Beneath the bird's glassy stare are saddles, faded photographs and books on western women and western poetry. Everything is assembled around an enormous fireplace.

This being a working ranch, I have come here, as many people do, to work. Though G Bar M Ranch accepts guests, it does so with an understanding that they will participate in the operating requirements of a Montana farm.

Greetings are therefore brief. There's a hasty tour of my room, which features an American flag hung above the quilted bed, before my short life as something approximating a makeshift cowboy begins.

It is immediately clear that the presiding authority here is Leffingwell, a ginger-moustached man who sits at the head of the table and commands his household with a disarming soft-spokenness. Whenever he asks somebody to milk a goat, for example, they do so not because he is the "boss", but because he is the sort of person you want to impress. After the meal, when local students exit the lodge to resume a class in shoeing horses, the remaining members (including me) turn to watch him insert tobacco behind his bottom lip and talk through a list of chores: a leak in the homestead, a tractor that must be lifted onto a truck, things to patch up, salt-lick for the cattle.

Sam, a cowhand for the summer, is sent to mend equipment. Ariane, from Paris, remains behind to help Maria. Only two hours after arriving, I find myself riding shotgun to a neighbouring property for a lesson in the art of inseminating cattle. Thankfully, it's a visual demonstration: my participation is limited to chasing heifers in a circle and holding open the holding shed door so Leffingwell can see what he's doing and the cows, each taking their turn, cannot.

Guest ranches are a common sight across Montana and the surrounding states. Indeed, their popularity seems to be increasing, with ranch rodeos back in vogue with colourful events such as branding and wild-cow milking. Since the railroad came through these parts in the late 19th century, homesteaders have opened up their homes to visitors and, in many cases, romanticising "dudes" - city dwellers with a penchant for fantasising the American west. While history books record, over time, a growing ambivalence on the part of westerners towards their eastern compatriots, the Montana homesteaders have nevertheless been more than happy to take their money.

Many of the dude ranches that exist today are holiday properties with carefully trimmed tennis courts alongside horses and fly-fishing expeditions. What Leffingwell offers is slightly different. There are no tennis courts, massages or internet reception.

G Bar M Ranch is also motivated by the faded idea that gave rise to guest ranches in the first place: a desire to celebrate and preserve a culture in peril. "We're trying to really teach some of the sustainable agriculture and livestock handling skills that are not lost, but becoming extinct," Leffingwell says.

To this end he intends to co-operate with a local movement of ranchers who have voluntarily added a clause to their deeds, prohibiting any major changes to property in the future. Its purpose is to safeguard the open spaces (often called the "big sky"), as well as the cultural and aesthetic heritage of Montana. Pull up a chair after dinner and ask him about his history and you'll realise just how much Leffingwell actually has worth protecting.

The night I do so, the clouds have broken into rain and the temperature has dropped enough to warrant a fire. Tobacco at the ready, Leffingwell begins an engrossing tale that starts with his great-grandfather George in 1898 buying a ticket on the railroad as far as he could go. Finding himself at the terminus point of Big Timber, Montana, George crawled off the train and got a job herding sheep. "After working for a while, he more or less saved up enough money to explore out. He came into this valley in about 1901, then went ahead and bought a homestead. And he set up camp and began building a ranch."

What follows is a labyrinthine saga involving railroad magnates, "saddle tramps", blind Braille teachers and Indian burial sites. It finishes, for now, with Mary Leffingwell, aged 15, the fifth generation on the land.

Knowing this story makes me notice small, time-worn details I'd previously overlooked. In the morning, I help distribute baled hay to the horses on the neighbouring property. When I return it's to a ringing bell, calling everyone to supper like the formal start of an old and cherished ritual. On my last day I'm asked to ring the bell myself. Sam, the cowhand, in a wide-eyed whisper that is only partly ironic, calls it "an honour". Sam also takes me fishing at the swollen creek, overturning rocks and logs in search of worms to use as bait. It's a gesture that casts us back to a world before digital distractions, further cementing my impression of having fallen out of time here.

Though everything from cattle dogs to the elk sausages on the table contribute to the ranch "experience", the daily focus is on the horses. Guests average four to seven hours a day in the saddle. They can, if they wish, tend to the upkeep of their own horse for the duration of a stay.

Leffingwell also offers dedicated classes in horsemanship. While I ride out several times over a few days, my first time, to check on cattle grazing alone in the mountains, is also the most memorable. After grooming and fitting a bridle, Leffingwell leads my horse out of the barn and into a muddy clearing, where more than two dozen other horses watch me mount and ride through the surging overspill from the nearby creek.

Later, recognising my struggle to fully command the horse, a fellow rider pulls up beside me and says in that vague way of the cowboy: "There is a void between a man and a horse. That void will be filled, either by the man or by the horse. Do you understand what I'm saying to you?"

Following our sighting of the Crazy Mountains, we turn into a series of high hollows, Leffingwell casting ahead in search of the cattle. After what seems, with increasing suspense, destined to end in failure, we come across them sitting calmly in a field.

Then the cattle dogs shoot off, unhinged by excitement. Leffingwell scowls. Their sudden action has startled some pregnant horses resting in the herd. A foal flees over the crest of the hill, followed by three mares.

Though we attempt to follow them through several stony passes, there's little chance of catching them today. Resigned, the group heads towards home, pausing on the final hill to observe the ranch in its quiet corner of the world.

Right then, as someone turns around and catches sight of the renegade horses watching us from a distant ridge, I'm reminded of something else Leffingwell had told me the night before.

"To survive as a horse here you have to handle well enough that I can crawl onto you and go and do a day's work whenever I have to," he'd said. "But I feel about them as somebody feels about their favourite car. And get them out on those hills . . . it's pretty darn neat."

All creatures great and small

MONTANA is known as a place of horse whisperers, but there's a great deal more worth seeing in the land of the "big sky".

For budding paleontologists, a statewide Dinosaur Trail takes in the breadth of natural history hidden beneath the prairies and badlands. This is the home of T-Rex, after all. A highlight is Makoshika State Park and Dinosaur Museum in Glendive; it's also possible to join dinosaur digs in Custer County. See mtdinotrail.org, custer.visitmt.com.

Montana has an unusually large number of "blue ribbon" trout rivers, meaning recreational fisheries of extremely high quality (see visitmt.com for a full list). Fly fishing is an obsession here and outfitters are available across the state to get you equipped.

For a different approach to the water, consider a float trip down the Yellowstone River, which varies from calm to Class IV white water. A good place to start is Gardiner, just outside the north entrance to Yellowstone National Park (three of the park's five entrances are in Montana); see wildwestrafting.com.

The Great Montana Sheep Drive started in the town of Reed Point as a joke. Now it attracts thousands of people who come to see woolies driven down the main street for Labor Day. This year's drive happens this weekend.

Lance Richardson travelled courtesy of Montana Tourism and V Australia.

FAST FACTS

Getting there

V Australia has a fare to Montana for about $1720 low-season return from Sydney and Melbourne including tax. You fly to Los Angeles (about 14 hr non-stop), then Delta Airlines to Salt Lake City (2hr), then to Bozeman (80min). G Bar M Ranch is about an hour's drive from the airport, through the town of Clyde Park. Australians must apply for travel authorisation before departure at https://esta.cbp.dhs.gov.

Working there

Though G Bar M Ranch takes direct bookings (gbarm.com), a better option is to go through Montana Bunkhouses. This self-described "matchmaking service" draws from a pool of 20 working ranches, personalising each experience to an individual's abilities and interests. Prices range from $US200-$US350 ($189-$330) a day. Phone +1 406 222 6101, see montanaworkingranches.com.

More information

See visitmt.com.

Read more: http://www.smh.com.au/travel/beneath-the-big-sky-20110901-1jnjk.html#ixzz1WqBTwcFB

No comments:

Post a Comment